The day Julius Caesar decided to reset time: the longest year in history lasted 445 days

Why a desperate attempt to fix Rome’s broken calendar turned 46 B.C. into the longest year ever recorded.

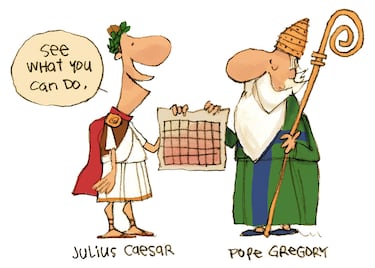

In 46 B.C., Rome experienced a year that seemed endless. Julius Caesar, working with an Egyptian astronomer, added extra months to fix centuries of calendar errors and realign the seasons. The result was the Julian calendar, the foundation of the one we still use today.

Believe it or not, that year lasted 445 days. It really happened, in Rome, and it became known as “the Year of Confusion.” Caesar had grown tired of spring festivals falling in the heat of summer and decided the calendar chaos had gone on long enough.

At the time, Romans followed a lunar calendar that depended heavily on the whims and political interests of religious officials known as pontiffs. The seasons drifted freely. A farmer might be celebrating planting season while the sun scorched the fields during the month of Sextilis, what we now call August. Planning anything long-term was nearly impossible.

Fixing time itself

Caesar was not just a general. He was also pontifex maximus, Rome’s chief religious authority. He turned to Sosigenes of Alexandria, an Egyptian scholar from a culture that had tracked time by the sun for centuries. The request was simple in spirit: design a calendar that actually worked.

Sosigenes proposed abandoning lunar cycles in favor of a solar year. The plan called for 365 days plus a quarter day, with an extra day added every four years. On paper, it was elegant. In reality, there was a massive backlog of errors to correct.

To balance the books, Caesar did what felt like adding overtime to a never-ending game. He inserted the traditional intercalary month, Mercedonius, which lasted about 23 days, and then added two more months, one 33 days long and another 34 days long. The final tally pushed the year to an astonishing 445 days.

Chaos across the empire

Daily life during this stretched-out year was predictably messy. Fixed payments and bureaucratic deadlines became a nightmare. Tenants wanted to pay rent for a year, while landlords argued the year now felt more like a year and a half. Any agreement tied to time suddenly became a legal headache.

Religious festivals dragged on, contracts turned into logic puzzles, and jokes spread through Roman taverns. Some historians speculate that Caesar may have used the confusion to accelerate legal deadlines or collect more taxes, though there is no surviving document to prove it. What is clear is that politics never disappeared from timekeeping.

The gamble paid off. In 45 B.C., the Julian calendar officially began. It remained in use across the Western world until 1582, when the Gregorian calendar refined the leap year system. Under the Julian model, a small error added up to one extra day every 128 years.

When the Gregorian calendar was adopted in Spain in 1582, the date jumped straight from Oct. 4 to Oct. 15. Those missing days simply never existed. Some countries, including Russia, continued using the Julian calendar well into the 20th century.

How Roman months came to be

The story gets even more intriguing. Long before Caesar’s reform, the Roman calendar had only 10 months, starting in March and ending in December. The roughly 61 days of winter were not counted at all.

That changed in 713 B.C., when Numa Pompilius, Rome’s second king, added January and February. He avoided even numbers, which were considered unlucky, and left February with just 28 days so the year would total 355 days, an odd number thought to bring good fortune.

Over time, pontiffs manipulated the calendar to suit their political needs. If an official’s term was set to end in December, inserting an extra Mercedonius could conveniently extend the year and keep him in power longer. Caesar’s reform not only realigned the seasons, it also eliminated a powerful political tool.

Why July and August bear famous names

The goal of the reform was to align Dec. 31 with the winter solstice. As a result, Jan. 1, 45 B.C., began with the Julian calendar perfectly synchronized with the sun. Sosigenes’ Egyptian model convinced Caesar that the only solution was to start fresh.

Adding roughly 80 extra days was like tacking two and a half months onto the season. The aim was simple: make spring spring again, not a misplaced celebration in Quintilis, the month we now know as July.

That month was renamed Iulius by the Roman Senate in 44 B.C., after Caesar’s assassination. It marked his birth month and many of his greatest victories. To this day, July carries his name.

Only one other month honors a historical figure. August was renamed in 8 B.C. for Caesar Augustus, Rome’s first emperor. Two of the most influential figures in Roman history are still with us every time we check the calendar.

A year that made time make sense

So the next time you glance at a calendar, remember Julius Caesar and the year that seemed to last forever. Behind every date is a story, and this one stands out: a 445-day year created so time itself could finally make sense again.

Related stories

Which country celebrates New Year’s first?

U.S. stock market trading times at New Year

Get your game on! Whether you’re into NFL touchdowns, NBA buzzer-beaters, world-class soccer goals, or MLB home runs, our app has it all.

Dive into live coverage, expert insights, breaking news, exclusive videos, and more – plus, stay updated on the latest in current affairs and entertainment. Download now for all-access coverage, right at your fingertips – anytime, anywhere.

Complete your personal details to comment