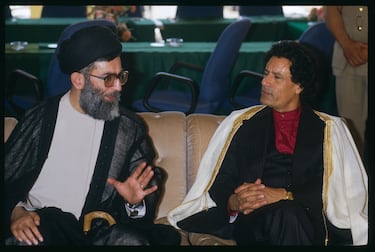

Who is Ali Khamenei, the Supreme Leader of Iran who succeeded Khomeini in 1989 and continued the Islamic Revolution?

From war and sanctions to regional influence, Khamenei has steered Iran for more than three decades while facing mounting domestic and international pressures.

Ali Khamenei, the Supreme Leader of Iran since 1989, has faced sanctions, international isolation, internal unrest, growing calls for political and social change, and even a short war with Israel under the shadow of Donald Trump’s presidency.

Khamenei’s presence dominates Iran’s political architecture, yet his vision has increasingly drifted from the daily lives of ordinary Iranians. While he champions a narrative of resistance, self-reliance, and revolutionary purity, the country struggles with crippling sanctions, rising inequality, and a young population that no longer identifies with that rhetoric. This gap reveals a leadership rooted more in the epic memory of 1979 than in the realities of the 21st century. Global attention and tension remain high.

From Mashhad seminaries to the presidency

Born in Mashhad in 1939, Ali Khamenei became the central figure of power in the Islamic Republic following the death of Ruhollah Khomeini. His path combines traditional Shia religious education, revolutionary activism, and a long political career that included serving as Iran’s president from 1981 to 1989. He was then chosen as Supreme Leader by the Assembly of Experts, overseeing both domestic policy and Iran’s regional strategy.

Khamenei came from a family of religious scholars, with his father serving as a local cleric. He studied in the seminaries of Mashhad, Najaf, and Qom under the guidance of prominent ayatollahs, including Khomeini himself. This training helped him build networks within the Shia clergy and gain recognition as a mujtahid, or expert Islamic jurist, though unlike Khomeini, his religious authority was initially more contested and relied on political consensus among revolutionary elites.

His time in Najaf and Qom also exposed him to transnational Islamist networks and militant political Islam, shaping the doctrine that would guide the Islamic Republic. In the years leading up to the 1979 revolution, Khamenei was a close collaborator of Khomeini, participating in underground anti-Shah activities and enduring arrests by the SAVAK, Iran’s pre-revolution intelligence service.

After the revolution, he held key positions: a parliamentary seat in the first Islamic Consultative Assembly, membership in the Assembly of Experts, and the presidency during the Iran-Iraq war. His executive experience, loyalty to Khomeini, and skill in mediating factions were decisive in his 1989 election as Supreme Leader, even though he was not yet a grand ayatollah in the traditional sense.

Continuity of the Islamic Revolution

As Supreme Leader, Khamenei has ensured the continuity of Iran’s revolutionary project, a theocratic-republican system guided by the principle of velayat-e faqih, or the rule of the Islamic jurist. His tenure has emphasized deep mistrust of the West and a narrative of resistance against the United States and Israel.

Under his leadership, institutions such as the Guardian Council and the Expediency Discernment Council have been strengthened, and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) has solidified its role as a central military, economic, and ideological force. Scholars note that Khamenei has refined a system of “factional balance,” allowing limited competition among conservatives, pragmatists, and reformists while retaining ultimate authority over strategic decisions, including the nuclear program, regional policy, and internal security.

Analysts highlight that his style is less charismatic and more institutional than Khomeini’s, relying on networks, security forces, and the IRGC to manage crises like the 1999 student protests, the 2009 Green Movement, and recent anti-regime demonstrations. This blend of selective repression, elite co-optation, and ideological control has preserved the system while widening the gap between the state and much of Iranian society.

Regional influence and resistance strategy

On the international stage, Khamenei has been the chief architect of Iran’s foreign policy, promoting an “axis of resistance” against the United States, Israel, and regional allies. Under his direction, Iran has built networks of allied groups, including Hezbollah in Lebanon, Shia militias in Iraq, support for Bashar al-Assad in Syria, and ties with Houthi rebels in Yemen. These alliances allow Iran to project asymmetric power and deter direct attacks. Scholars note that this approach has fueled rivalries with Saudi Arabia, Israel, and other Gulf states, culminating in a particularly difficult 2025 after a brief 12-day war with Israel.

The Iranian nuclear program is another cornerstone of his strategic legacy. Khamenei has publicly stated that Iran does not seek nuclear weapons for religious or ethical reasons but insists on the country’s right to develop civilian nuclear technology and advanced deterrence capabilities. He played a key role in both authorizing the 2015 nuclear deal and responding after the U.S. withdrawal in 2018, gradually increasing uranium enrichment as a tool of leverage.

Global relationships

Khamenei has cultivated strategic ties with countries that share Iran’s opposition to U.S. dominance. Tehran has deepened relations with Russia, especially under Vladimir Putin, in military, energy, and diplomatic arenas, including coordination in Syria and cooperation within the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Relations with China have also grown, resulting in long-term agreements on energy, infrastructure, and technology under the Belt and Road Initiative.

Within the Muslim world, Khamenei maintains a complex network of alliances: rivalry with Saudi Arabia and Gulf monarchies, and alignment with governments or movements that share anti-Western or Islamist agendas. His relationships with Iranian presidents, from Rafsanjani to Raisi, have ranged from tactical cooperation to tension, always under the premise that the Supreme Leader defines the red lines for foreign and security policy.

Public image and legacy debates

Beyond geopolitics, Khamenei projects an image of a religious-intellectual leader who enjoys poetry and literature, holding meetings with poets and weaving literary references into his speeches. This cultural side reinforces his role as a moral guide, although critics argue it does little to offset the authoritarian nature of his rule.

Academic studies suggest Khamenei’s legacy will be defined by paradox: he has preserved the Islamic Revolution and made Iran a regional power, yet his tenure has been marked by sanctions, partial isolation, domestic tension, and rising demands for political and social change.

Succession is seen as a critical test for the resilience of the system he has shaped. The key question is whether post-Khamenei Iran will continue prioritizing resistance and asymmetric regional influence or pivot toward a more pragmatic approach in the global order.

Related stories

Get your game on! Whether you’re into NFL touchdowns, NBA buzzer-beaters, world-class soccer goals, or MLB home runs, our app has it all.

Dive into live coverage, expert insights, breaking news, exclusive videos, and more – plus, stay updated on the latest in current affairs and entertainment. Download now for all-access coverage, right at your fingertips – anytime, anywhere.

Complete your personal details to comment