On July 24, 1982, the ‘Son of the Wind’ jumped further than anyone in history but, despite no mark on the plasticine, the officials ruled it invalid.

The day Carl Lewis jumped a record 30 feet but it didn’t count: “incompetent and stubborn”

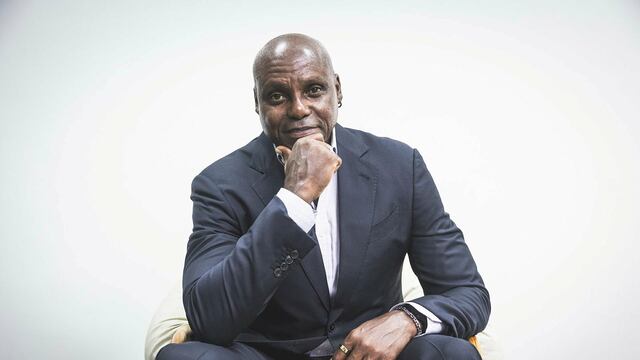

“It was the fault of an incompetent and stubborn official,” Carl Lewis recalled in an interview with AS. The “Son of the Wind,” winner of nine Olympic gold medals and eight World Championship titles, was referring to the official responsible for watching the takeoff board during the long jump at the U.S. National Sports Festival on July 24, 1982, in Indianapolis. On that hot summer day, at 719 feet above sea level, the history of long jump could have been rewritten.

A 20-year-old prodigy who had already jumped 28 feet 3.5 inches (8.62 meters) the year before was on the verge of erasing Bob Beamon’s iconic 29 feet 2.5 inches (8.90 meters) from the history books. It would be nine more years before that legendary 1991 World Championships final in Tokyo where Mike Powell jumped 29 feet 4.25 inches (8.95 meters) and Carl Lewis had four attempts over 28 feet 10.5 inches (8.80 meters), including one invalidated by wind (29 feet 2.75 inches, or 8.91 meters) and his official personal best of 29 feet 1.25 inches (8.87 meters), which still ranks as the third-best jump in history.

“It was the fault of an incompetent and stubborn official”

Carl Lewis

What happened during Carl Lewis’s 1982 long jump controversy?

Back on that scorching July day, Lewis was competing in both the long jump and the 4x100m relay, in a team made up of Calvin Smith, Stanley Floyd and Mike Miller, representing the southern United States team in the event that pitted teams from the four corners of the country against each other. Yes, that’s right. The Alabama native, now 64, paused between jumps to run his relay leg.

That didn’t stop him from putting on an incredible performance… despite the fact that his first four attempts were ruled invalid. His valid jumps were recorded at 28 feet 9 inches (8.76 meters) and 28 feet 0.75 inches (8.55 meters), but the real story was in his fourth leap.

Could Carl Lewis have broken the 30-foot barrier in 1982?

Here’s where it gets interesting. On his first attempt, “King Carl” landed beyond the 30-foot mark. Invalid. The crowd, packed with 13,000 spectators, went from roaring excitement to gasps of disappointment upon seeing the ruling. But hope returned quickly as everyone realized they might be witnessing history. Before his second attempt, Lewis had to run the 4x100. He and his teammates clocked 38.27 seconds, the sixth-fastest time ever. His next jump was identical to the first—again landing beyond the 30-foot mark and barely touching the takeoff board. His form was flawless; it was only a matter of a few centimeters on his foot placement. The relay medal ceremony once again disrupted his concentration. After receiving his medal, he removed it from his neck and headed back to the long jump runway. Another invalid attempt, this time clearly shorter.

Then came the moment. It was the first jump he could truly focus on without distraction. His friend Jason Grimes made sure the stadium fell silent. Even Dwight Stones, high jumper and ABC Olympics commentator, quieted down after being called out by Grimes. There was a palpable sense of anticipation in the air. Lewis began his run, reaching incredible speed before taking off with his right foot and unleashing his full power in the air, landing in the sand. He glanced over as the crowd erupted in joy. The mark was well beyond the 30-foot line. Legal wind, no mark on the plasticine. Spectators quickly calculated the distance: “Thirty feet!” someone shouted. In fact, according to Grimes, the world long jump silver medalist, who was just inches from the pit, it was a full 30 feet and 2 inches (9.19 meters).

Why was Carl Lewis’ historic jump ruled invalid despite no proof of a fault?

But the jubilation lasted only a few seconds. A small red flag waved from the right arm of the official at the takeoff board. Carl Lewis approached him, checked the board—no footprint on the plasticine. He asked for an explanation. He knew the jump was valid; he hadn’t touched the red zone. This is an athlete who surpassed 28 feet (8.53 meters) 71 times in his career. Even his rivals joined in the protest. They had all witnessed the best jump in history—one that would still be the greatest today by far. The only jump over 30 feet.

The three officials conferred and decided to apply an NCAA rule typically used in collegiate competitions: despite no mark on the plasticine, they believed that the tip of Lewis’s shoe had crossed the board by mere millimeters. It was their visual perception. There was no video, no replay system in that era to prove it… or to disprove it. It was 1982, after all.

Carl Lewis’ jump was ruled invalid, even though the IAAF (now World Athletics) rule states that if there’s no mark and the fault can’t be proven, the jump should be considered valid. Even TAC, now USATF, determined that the NCAA rule shouldn’t have been applied because this wasn’t a collegiate event. It was all in vain. The judges stood firm. To make matters worse, the head official ordered the sandpit attendant to quickly rake over the mark before it could be measured and possibly lead to future protests. “The judge went out of his way to tell the pit guy to rake the jump to prevent it from being measured. It was all very crude,” Lewis would later reveal in an interview.

“The judge went out of his way to tell the pit guy to rake the jump to prevent it from being measured.”

Lewis on the day's events

“Lewis Wuz Robbed” headlined Jim Dunaway in Track & Field News, the only in-depth article ever printed about the competition. No quality photos exist, and only a few grainy videos can be found on YouTube. Bob Beamon’s 29 feet 2.5 inches would continue to hold the world record. Carl Lewis’s earth-shattering 30 (or more) feet will never be reflected in the record books.

Related stories

Get your game on! Whether you’re into NFL touchdowns, NBA buzzer-beaters, world-class soccer goals, or MLB home runs, our app has it all.

Dive into live coverage, expert insights, breaking news, exclusive videos, and more – plus, stay updated on the latest in current affairs and entertainment. Download now for all-access coverage, right at your fingertips – anytime, anywhere.

Complete your personal details to comment