Jordan, Shaq, Harden... The players who led to NBA rule changes

We take a look at how the impact of some of the NBA's most memorable players, such as Michael Jordan and James Harden, has forced the league to change the rules of the game.

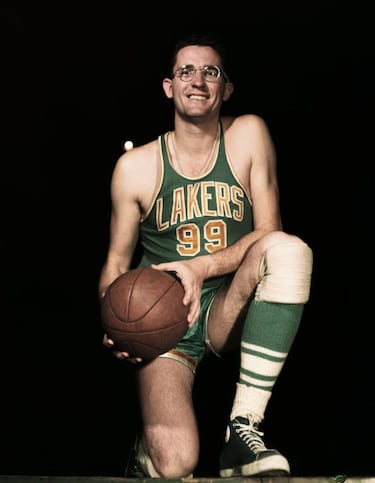

George Mikan: the first dominant big man

Beginning in the period before the BAA and the NBL merged to become the NBA, the emergence of George Mikan as the first dominant star of the game changed everything. With the Lakers, who were still based in Minneapolis, 6' 10" center Mikan won five titles between 1949 and 1954 and was perennially the league’s leading scorer, surpassing 28 points per game at his peak, with rudimentary movements in the post which, at the time, were unique. That, allied with his size, made him an unstoppable player. To avoid Mikan simply devouring his opponents close to the rim, the league responded by introducing what became known as the Mikan Rule, which widened the lane, the area below the basket where players can only spend three seconds, from six to 12 feet. (The lane would later be expanded again, because of Wilt Chamberlain). It was the first attempt to move a dominant big man away from the basket, as a game still in construction adapted to a new profile of star. Mikan’s shot percentages dropped from almost 43% to 38%.

Mikan also leads to introduction of shot clock

In 1954, the NBA adopted the shot clock, which gave the team in possession 24 seconds to go for the basket or lose the ball. Again, Mikan had a major influence on the introduction of the rule. Firstly, because he led a team whose slow style of basketball suited his game, and secondly, because the Lakers’ opponents would try to keep possession for as long as possible, as a stalling tactic designed to avoid the ball reaching him. Things came to a head in the Lakers’ infamous 19-18 defeat to the Fort Wayne Pistons, in what remains the lowest-scoring game in BAA, NBA and ABA history. Mikan scored 15 points, his team-mates managed three between them, and the Pistons believed they had found the way to to stop the center. However, the league reacted by implementing the shot clock, a rule that transformed the game’s speed and intensity.

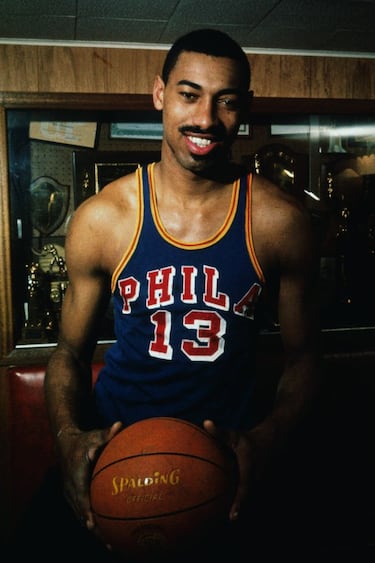

Wilt Chamberlain's emergence in Kansas

The holder of many long-standing NBA records and a player who many considered Superman amongst mere mortals, Chamberlain had a transformative effect on a game that wasn’t ready for the physical prowess of a center who remains the only man to score 100 points in an NBA match. While a college player at Kansas (1956-58), his dominance led to the banning of offensive goaltending, a rule which prevents players from interfering with the ball when it is on the way to the basket, is on a downward path and is above the ring. Other rules were changed to adapt to him while he was in college basketball: inbounding the ball over the backboard was banned, preventing team-mates from teeing Chamberlain up for a simple dunk, and it became against the rules to cross the free-throw line after taking a free-throw, as he tended to sink the rebound from his own shot, in the process scoring two points instead of one.

Chamberlain's arrival sows terror in the NBA

Following a spell with the Harlem Globetrotters, Chamberlain then began his career in the NBA, leading to a number of changes resulting from the arrival of a player who averaged more than 37 points and 27 rebounds as a rookie, with the Philadelphia Warriors. By his third season, before the franchise moved to San Francisco, he was at 50.4 points and 25.7 rebounds. In a bid to reduce his total domination of the play in and around the lane, the NBA widened the three-second area to 16 feet. The aim was to move Chamberlain away form the basket at least a little. The measure was adopted in 1964 and reduced his percentages to a degree.

Bill Russell: the reign of the Lord of the Rings

The emergence of great centers, giants who dominated games at will and created dynasties, transformed early basketball, and the NBA then remained largely unchanged until the arrival of Magic Johnson and Larry Bird in 1979. In addition to Mikan and Chamberlain, it’s clear that Bill Russell also had a major influence on rule changes governing the lane’s distance from the basket and, above all, defensive and offensive goaltending. Russell was one of the first masters of the game above the rim, the first great anchor in defence and a unique intimidator. With his 11 championship rings, he beat Chamberlain time and again in the playoffs, limiting the latter to just two NBA titles despite his stratospheric figures. Russell, 6’ 10” tall and with a 224cm wingspan, changed the way basketball is played close to the rim, and was the driving force behind the quick transitions of Red Auerbach’s Boston Celtics. He surpassed 1,000 rebounds in 12 consecutive seasons, and he and Chamberlain remain the only players to reach 50 rebounds per game. Both at the University of San Francisco and the Celtics, Russell was one of a trio of legendary centers who helped transform the rules of basketball and the way it is played.

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: the NCAA slams dunks

Before changing his name and becoming Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Lew Alcindor began carving out his giant chapter in the history books at UCLA. It was the start of a legendary career for a player who, until the arrival of LeBron James, was the only man who could legitimately challenge Michael Jordan for the status of the NBA’s best ever. After winning 71 games in a row on the high-school circuit in New York, he joined John Wooden’s UCLA team and, measuring 7’ 2”, proved unstoppable. Between 1966 and 1969, UCLA won three straight titles, with Alcindor the MVP and Final Four MVP on each occasion. He averaged 26.4 points and 15.5 rebounds as his team registered a record 88 wins and just two defeats in 90 games: 30-0 one year, 29-1 in the other two. Such was UCLA's superiority that the NCAA banned dunks, which had not only helped to make Alcindor so effective but had even come to be considered disrespectful to opponents who had no hope of getting in his way. The Lew Alcindor Rule remained in place in high-school and college games between 1967 and 1976, and the center’s response was to perfect other ways of scoring, leading to the creation of the most unplayable shot in history: his memorable Skyhook.

Louie Dampier: the first three-point specialist

Nowadays, it’s impossible to imagine the NBA, or the game of basketball, without the three-pointer, which has sparked a revolution in the way teams score, play and build their rosters. But, of course, it wasn’t always like that. Indeed, there were no threes in the NBA until the end of the 1970s. It made its debut in the 1979/80 season, Chris Ford of the Celtics sinking the first three-pointer in a 12 October game against the Rockets - clash that was also Larry Bird’s first game as a professional. Up to then, the purists had been suspicious of what they branded a ‘fairground trick’, and indeed the shot took a while to become more than a scarcely-used resource. The three-pointer had been tried out in high-school competitions since the 40s and first appeared at professional level in the ABL, in 1961. Its chief point of lift-off came in the crazy and unforgettable ABA, which was a competitor to the NBA until their merger in 1976. In the irreverent and spectacular ABA, the three-pointer was something that set it apart from the NBA, and the first three-point king was Louie Dampier, a star at college team Kentucky and then with the Colonels in the ABA, where he was the leading scorer of threes (794) thanks to seasons such as 1969/70, when he registerd 2.4 per game with an almost 40% success rate. A true specialist who, after the ABA-NBA merger, finished off his career at the San Antonio Spurs.

Darryl Dawkins: the alien from another planet who forced a basket redesign

Darryl Dawkins wasn’t a dominant center, although his unquestionable talent means he could have been one had he possessed a greater work ethic. But he was one of the most loved and charismatic characters of his era. Dawkins, who was nicknamed ‘Chocolate Thunder’, measured 6’ 11”, weighed 251lbs and played in the NBA between 1975 and 1989, before spells in Turin and Milan. Stevie Wonder gave him his moniker and he became synonymous with a powerful dunk that shattered the backboard twice in 1979. NBA commissioner Larry O’Brien told him that if he broke a third, he would be suspended and fined $5,000, and at the end of that season, the league redesigned the basket and backboard, lending the structure greater flexibility to allow it to withstand the tremendous strength of a new generation of dunkers. The next player who earned a reputation for breaking the backboard was Shaquille O’Neal, many years later. Dawkins memorably said that he was an alien who had come from the planet Lovetron, where he practised what he called ‘interplanetary funkmanship’ with his girlfriend Juicy Lucy. He called his first backboard-breaking dunk 'The Chocolate-Thunder-Flying, Robinzine-Crying, Teeth-Shaking, Glass-Breaking, Rump-Roasting, Bun-Toasting, Wham-Bam, Glass-Breaker-I-Am-Jam'.

Pat Riley: the perennial All-Star coach

This rule change wasn’t brought about by a player and doesn’t directly affect the game, but this is a good place to look back at the reason why a coach cannot represent their conference in two straight All-Star Games. The All-Star teams are in theory led by the coaches whose franchises have the best record in their respective conference, but amid the Lakers’ domination of the Eastern Conference in the 1980s, their head coach, Pat Riley, earned the right to lead the East’s All-Star team in eight out of nine seasons between 1982 and 1990. To keep things interesting, the NBA introduced what is known as the Riley Rule, which bans consecutive All-Star appearances by a coach. In such a scenario, the coach of the conference’s second-best team gets the nod instead.

Michael Jordan and the 'illegal offense' call

The emergence of Magic Johnson and Larry Bird put paid to the old NBA adage that to play well you need a great point guard, but to win titles you need a great center. The new NBA of the 1980s then lifted off into the stratosphere after the 1984 arrival of Michael Jordan, who went on to win six championships, six finals MVP awards and five regular season MVPs, and end the campaign as the highest scorer on no fewer than 10 occasions. In the Jordan era, characterised by a new way of attacking focused almost exclusively on a good outside shooter, the 'illegal offense' call came into being. The rule banned teams from positioning three players with no intention of participating in the play behind the three-point line, to leave the shooter in question alone in space to go for the basket. “There has been a growing propensity among coaches to move three men above the top of the key, thus clearing the way for two-man games or individual forays like those of Chicago's Michael Jordan,” the Washington Post noted in 1987, the year the rule was introduced. “According to Rod Thorn, the league's vice president in charge of operations, those isolation tactics were 'getting away from what the game is about'."

Reggie Miller: the NBA kicks out kicking out

Curiously, the Reggie Miller Rule was implemented seven years after the 2005 retirement of the legendary Indiana Pacers shooting guard, who was one of Michael Jordan’s chief rivals in the East in the 1990s. Miller remains the third-top scoring three-point shooter in history, behind Ray Allen and Steph Curry, with 2,560 successful threes. In a time with fewer such specialists, Miller’s quickfire catching and shooting made him one of the most charismatic players of his era. He was a player who perfected the art of kicking his legs out as he jumped to shoot, forcing contact with the defender and winning free throws. The move became so widely used in the NBA that the league began to punish it in 2012, with referees instructed to give an offensive foul instead.

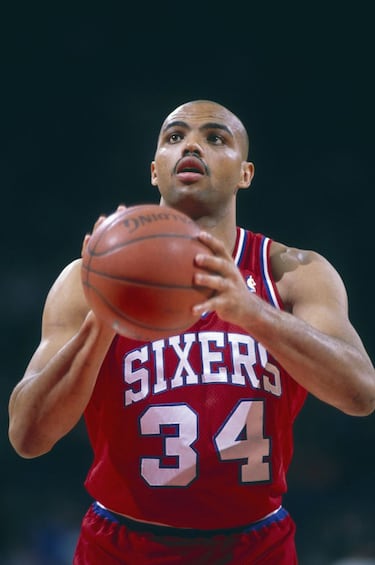

Charles Barkley and the 'five-second back to the basket violation'

The ‘five-second back to the basket violation’, also known as the Charles Barkley Rule, is unique to the NBA and appeared in 1999. The rule prohibits players from dribbling the ball with their back or side to the basket for more than five seconds if they’re between the free-throw line and the basket. It was a response to the way Barkley, one of the greatest power forwards of all time and one of the best players never to win a championship ring, perfected the art of making the most of his physique in the post. A player of enormous strength and talent, he would receive the ball, place his back to the defender and begin pushing towards the basket. When he started to do it on every possession, it led to tedious, repetitive attacks, particularly when other teams began to imitate this tactic for creating easy scoring situations. The NBA’s response was to punish it with the loss of possession.

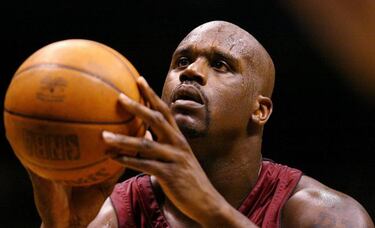

A force of nature called Shaquille

At his peak, Shaquille O’Neal dominated the NBA in a way few other players in the history of the league have been able to. After reaching the finals with the Orlando Magic, he left for the Los Angeles Lakers and formed a devastating partnership with Kobe Bryant, as the Lakers won three championships in a row between 2000 and 2002. Shaq, an irrepressible player close to the basket, was finals MVP on each occasion. After Darryl Dawkins, O’Neal was the next player who forced the NBA to redesign the backboard, to prevent him from breaking it with one of his brutal dunks. More importantly, from 2001 the NBA relaxed its rules on the number of defensive players in the lane, to allow teams to accumulate more bodies between players like O’Neal and the basket. The measure was accompanied by the introduction of the defensive three-second violation, which prohibits a defending player not actively guarding an opponent from spending more than three seconds in the lane.

Shaq and the 'hack-a' tactic

Another law change in which O’Neal was an obvious factor and, as with the Reggie Miller Rule, it was introduced after his retirement. The center called it a day in 2011 and, in 2016, the NBA brought in a measure aimed at avoiding the ‘hack-a’ tactic, which involved committing constant fouls on poor free-throwers in a bid to limit their impact, break up the rhythm of the game, reduce the other team’s productivity… Because of his terrible success rate from the free-throw line, ‘hack-a-Shaq’ was a common practice among O’Neal’s opponents, and began to spread to other players in the NBA, and was almost always employed in the closing stages of a game. The league’s changed rules seek to prevent such deliberate fouls in the last two minutes of each quarter. In that time period, such actions are punished with a free throw for the player fouled and the return of possession to his team.

The Bad Boys 2.0 and the change of tempo

Related stories

In the 1990s, basketball in the NBA became a tougher game. The tempo dropped, physicality and aggression increased, it was harder and harder to score and teams depended on their big men or on great individual scorers whose play was facilitated by offensive moves aimed at clearing their path to the basket. When Michael Jordan retired, the NBA was conscious of the fact that its product was less attractive to the wider public. In the 1999 finals, when the Spurs beat the Knicks 4-1 to win their first ever championship, TV ratings fell from their peak in 1998 (Jordan’s last title) to their lowest ebb since 1981. The possession count was the lowest it had ever been (88.9 per game), a trend that had begun with the Detroit Pistons’ Bad Boys at the end of the 80s and the beginning of the 90s, and culminated in another title-winning Pistons team, the Bad Boys 2.0, who played at a rate of 87.9 possessions and won the championship in 2004. That year, to foster a more open, watchable brand of basketball, the NBA brought in changes that have led to the current style of play, replete with ball circulation, spaces, three-point shots and a greater influence from backcourt players. It changed the defensive rules, optimised the three-second rule and banned hand checking: defenders can no longer place and keep their hands on an opponent if he isn’t close to the basket and with his back turned. Contact is not allowed to affect the offensive player’s speed, balance or rhythm. The first team to make the most of the new rules was the 'seven seconds or less' Phoenix Suns, led by Mike D’Antoni and Steve Nash. From there, basketball progressed to the offensive, three-point revolution that we’ve experienced in recent years.

James Harden and the sneakily-won foul

The last major change arrived this season, and has served to help the defender’s cause and made points-scoring, which had started to feel too easy in recent times, more difficult. The most notable player affected by the new rules is James Harden, although others such as Trae Young, Damian Lillard and Luka Doncic have also gained a lot of attention. The change to the laws of the game seeks to prevent players from forcing contact with defenders and winning free throws from fouls that they artificially bring about: plays in which the offensive player throws himself against the defender after feinting to shoot; positions his arm underneath the defensive player’s; stops suddenly to be bumped from behind… The NBA has instructed referees to stop punishing defenders in such instances, and the effect has been noticeable and well received.