New discovery suggests there could be water on Jupiter’s moon

Scientists believe that underwater snow may be present under Europa’s icy crust, a sign that there could be life in our solar system.

A recent discovery on Europa, a moon of Jupiter, has hinted at the possibility of life in our solar system. Beneath its thick icy crust, researchers suspect that there could be a huge ocean with lumps of snow flowing between inverted ice spikes and submerged gullies.

The unusual underwater snow is also known to form under ice shelves on Earth and the study suggests the same could be happening on Jupiter’s moon too. Underwater snow is much purer than other types of ice, meaning that that the ice cap on the moon Europa could be less salty than previously thought. This could help future studies into the body of water.

For researchers this brings the tantalising prospect of life being found in our own solar system. Europa is around 2,000 miles wide, making it slightly smaller than Earth’s moon, and it is becoming a serious contender in the search for life after scientists found evidence of an ocean buried 10-15 miles below the surface.

“Liquid water near to the surface of the ice shell is a really provocative and promising place to imagine life having a shot,” said Dustin Schroeder, associate professor of geophysics from Stanford University.

“The idea that we could find a signature that would suggest a promising pocket of water like this might exist, I think, is very exciting.”

Important discovery ahead of the next NASA mission

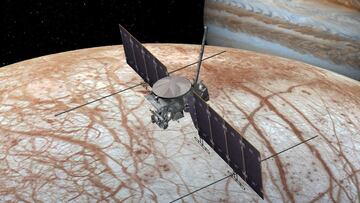

The Europa discovery is an important finding for the scientists preparing NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft, which will use radar to peer below the distant moon’s ice cap to see if Europa’s ocean could be hospitable to life.

The new information, suggesting that the water could be purer than first thought, could be critical to the mission’s success. Salt water trapped in the ice may affect visibility and limit the depths to which the radar can see below the ice sheet. Being able to predict what ice is made of may help scientists make sense of the data gathered.

Related stories

The study, published in the August issue of the journal Astrobiology, was led by the University of Texas, which is also leading the development of the Europa Clipper ice-penetrating radar instrument. The main author of the study, Natalie Wolfenbarger, has outlined the next steps for the mission:

“When we explore Europa, we are interested in the salinity and the composition of the ocean, because that is one of the things that will determine its potential habitability or even the type of life that could live there.”