Much more than a record-breaking baseball player, the legendary Hispanic star will be remembered for giving a voice to Black and Latino people everywhere.

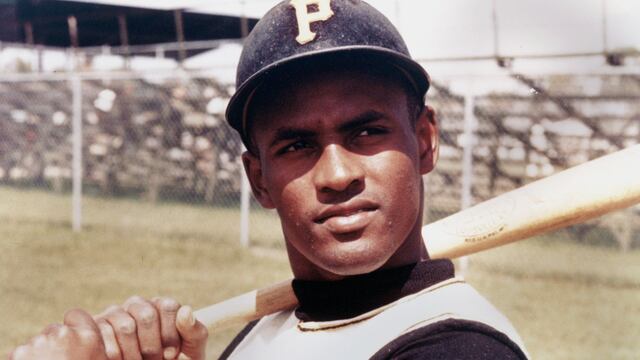

Hispanic Heritage Month: Rembembering Puerto Rican baseball star Roberto Clemente

It’s Hispanic Heritage Month and with that, we are focusing on the legendary Puerto Rican player, Roberto Clemente. One part amazing, and two parts great guy, he was a legend both on and off the field.

Looking past Roberto Clemente’s tragic death

Over the last 50 years, the memory of Roberto Clemente has been largely defined by the tragedy that took his life at the young age of 38 years old. It was New Year’s Eve, 1972 and Clemente had chartered a plane to deliver supplies to earthquake victims in Nicaragua. Such was the nature of the man. Yet, sadly it was not to be as Clemente’s aircraft would crash just off the coast of his native Puerto Rico shortly after takeoff. Along with four others, Clemente preished in the crash.

Roberto Clemente Day is celebrated annually on September 15 across Major League Baseball, honoring the legendary player and humanitarian. This year, the Pittsburgh Pirates will be hosting their first ever live Spanish broadcast, with Roberto Clemente Jr. and Carlos Baerga. pic.twitter.com/8bRERy2qk2

— Iván Díaz-Carrasquillo, J.D., CCS, CFE (@IvanDiaz_PR) September 15, 2025

Now, while it’s completely understandable for grief and anguish to take center stage when a life is lost, sometimes it does us good to focus on what was left behind. Indeed, the incredible legacy that Roberto Clemente left behind is something that continues to inspire.

A selfless humanitarian, Clemente was fiercely committed to bettering the lives of people not just in his home country of Puerto Rico, but wider Latin America as well. “Obviously, everyone knows what he did on the field, but off the field, the work he did to help the people - not only in Puerto Rico, but in other Latin countries - this guy is unbelievable,” said Cardinals catcher and Puerto Rico native Yadier Molina. “You can learn from it.”

Who was Roberto Clemente the player?

To put things in perspective, Roberto Clemente was the first player from Latin America inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame. We’re talking about a player that possessed an unreal amount of talent. During his 18-year career with the Pirates, Clemente would win the World Series on two occasions, he would claim the Gold Glove award 12 times and there were also 15 All-Star appearances. Winner of the 1966 League MVP award, he was also the first Latin American player to reach the mythical 3,000 hit mark in the league.

The Pirates will honor Roberto Clemente with a first-of-its-kind broadcast Mondayhttps://t.co/oGkCqfM968

— SportsNet Pittsburgh (@SNPittsburgh) September 12, 2025

Yet numbers hardly do justice to the exhilarating sight of Clemente tearing around the bases or his breathtaking throws from right field. We also haven’t mentioned the blinding speed with which he would get around the bases or the majesty he’d display with his long throws from right field. The Puerto Rican was quite simply a show to behold.

Who was Roberto Clemente the man?

The youngest of seven children, Clemente understood the value of sharing from an early age. Unfortunately, he had also had an education - due to the times - in racism and bigotry and how it turn he could easily be subjected to it.

Indeed, when he arrived in the Major Leagues in 1955, eight years after Jackie Robinson became the first black player in history and nine years, before President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act into law, Jim Crow laws were still very much in place.

"I am more valuable to my team hitting .330 than swinging for home runs." ~ Roberto Clemente pic.twitter.com/E6arzKFsGU

— OldTimeHardball (@OleTimeHardball) September 14, 2025

Consider for a moment, that as an Afro-Latino man Clemente along with all other Black players of the time were not allowed to stay in the same hotels or share meals with their white teammates in restaurants.

This was ironically enough, completely foreign to Clemente who himself had grown up in a fully integrated Puerto Rican society as a child. “My mother and father never taught me to hate anyone, or to dislike anyone because of their race or color,” Clemente said in a television appearance in October 1972, which is considered his final interview with English-language media. “We never talked about that.” During that interview, Clemente - a former U.S. Marine Corps reservist – would also disclose that he was so indignant about having to wait on the team bus while his white teammates dined, that he demanded then Pirates general manager Joe Brown provide the team’s Black players with a car of their own to travel in.

Roberto Clemente didn’t back down

Yet another interesting thing to observe about Roberto Clemente was the manner in which he kept mainstream media on its toes. Often guilty of anglicizing his name to “Bob,” Clemente made it clear that he was not having it.

Even when they would mock his accent in classless fashion, he continued to challenge stereotypes about Latino players. Respect and dignity, were things that he maintained were the rights of he and his peers, even when some of them pressed him to hold his tongue.

"[He] was always advising them and making sure that they passed that forward for the younger kids coming into the league..."

— MLB Network (@MLBNetwork) September 14, 2025

Roberto Clemente Jr. discusses the impact his father had on Hispanic players during his career.

🎙️ MLB Network Podcast presented by @chevrolet pic.twitter.com/LzrtgAlsZD

“They told me, ‘Roberto, you better keep your mouth shut because they will ship you back,’” he recalled. “I said, ‘I don’t care one way or the other. If I’m good enough to play here, I have to be good enough to be treated like the rest of the players.’”

A Son of the Soil: Roberto Clemente was Puerto Rican but universal

Related stories

“[Clemente’s] influence on the culture of leadership in baseball is what gets lost,” says Adrian Burgos Jr., professor of history at the University of Illinois, who focuses on the participation of minorities in American professional sports. “Clemente was a figure who was not satisfied, was not acquiescent to those who refused to treat his people, Black and Latino, less than [they] treated the other individuals in baseball.”

An inside look at the Roberto Clemente Museum in Pittsburgh since his documentary is now released in select theaters. pic.twitter.com/qZgvNHSGuP

— World Baseball Network (@WorldBaseball_) September 12, 2025

If there was a moment when he succeeded in forcing that idea into American consciousness, it would have to be in 1971 when he became the first Latin American player to be named World Series MVP. During the series against Baltimore, Clemente would bat .414/.452/.759 and even hit the solo home run that would give Pittsburgh the 2-1 win in that fateful game 7. What did Clemente do when thrust into the national spotlight? The man who once stated that he belonged to “the common people of America,” spoke directly to national television cameras in the United States of America and asked his parents in Puerto Rico - in Spanish - for their blessing.

Complete your personal details to comment