The stark contrast in coverage and resources for the Titanic tourists and migrants on the Mediterranean

The media’s coverage of the search for the Titanic tourists is receiving backlash from activists who say the plight of migrants is consistently ignored.

As many in the United States and Europe have their attention drawn to the missing submersible, dubbed the Titan, carrying five people to the wreckage of the Titanic, there is another tragic story that took place at sea earlier this month that the media missed almost entirely.

On 14 June, off the coast of Greece in the Mediterranean Sea, a boat that set sail for Italy from Libya carrying between 400 and 700 migrants capsized. To date, the International Organization for Migration has confirmed seventy-eight deaths but believes this figure is likely much higher. A UN Human Rights agency reported on 16 June that five hundred migrants, including “large numbers of women and children,” were still missing and that only 104 people had been rescued. Since then, three more bodies have been recovered. The death count has yet to be finalized, but the horrific incident is likely to be one of the most deadly cases in EU migratory history.

Moreover, as investigations have progressed, discrepancies in the response by Greek officials have surfaced, suggesting that they were aware of the boat and its passengers’ distress but failed to provide assistance —a severe violation of international maritime law. In the hours and days after the tragedy, Helena Smith from The Guardian reported that the boat sank quickly after running out of fuel, based on information from survivors who spoke to reporters in the Greek media. However, other survivors later claimed that they had been asking for help for almost fifteen hours. This contradicts the statements of Greek officials, who claim that they offered assistance but were turned down by the boat’s occupants. Further analysis by The Guardian using “tracking data supplied by [...] MarineTraffic,” which was corroborated by the BBC, found that the boat carrying migrants “was stationary and clearly not advancing for up to seven hours.” The findings raise doubts about the validity of the initial claims that the boat sank rather quickly, which had aligned with the narrative provided by Greek officials that had been circulating in the country’s press in the days after the incident.

The media’s wall-to-wall coverage of the Titanic tourists

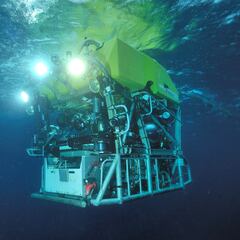

On the other hand, the disappearance of the Titan has garnered significant media attention since the vessel lost contact with the mainland on Sunday, 18 June.

There are three main reasons why this case has captivated the media and large portions of the public.

Firstly, the search and rescue mission represents a race against time, with officials estimating that the vessel only has enough oxygen to keep passengers alive through Thursday.

Another aspect to consider is the prominence of the passengers who purchased the $250,000 ticket for the journey. These individuals include British billionaire Harmish Harding, Pakistani businessman Shahzada Dawood, and his adolescent son. Furthermore, in addition to the three passengers, Stockton Rush, the CEO of OceanGates Expeditions, the firm providing the tour, and French navigator Paul-Henri Nargeolet are also onboard.

Thirdly, the fact that so few people have ventured down to the wreckage of Titanic, arguably one of the most notorious maritime events in modern history, generates a level of interest with viewers.

Emergencies and crises faced by refugees, those on and off the Mediterranean, may meet the first criteria, but lacking the other more sensationalized features, often lead the media to ignore the story. The lack of coverage then minimizes the scrutiny faced by governments who are obligated under international law to render aid to passengers in distress. Since 2014, the UN estimates that more than 27,000 migrants have perished while attempting to seek refuge while crossing the Mediterranean Sea. This year alone, more than 1,200 cases of missing people have been recorded by the organization.

The importance of safety was undermined by OceanGate’s CEO

The high cost to board the Titan is, in part, due to the danger associated with making it to such extreme depths of the ocean. However, the trail of public comments made by Rush highlights an egregious lack of respect for the dangers posed by the voyage and the safety precautions needed to keep those aboard safe. Last November, during an interview on the CBS News podcast Unsung Science with David Pogue, Rush was asked about the dangers of the trip and how his company accounted for them. Pogue said that Rush wasn’t “exactly an amateur” and noted that the vessel was loaded with ninety-six hours worth of oxygen even though the trip was only ten hours. However, the host also said that one’s “anxiety” is not likely to be quelled when Rush says that “at some point, safety just is pure waste” and that he believed that the vessel could be designed “just as safely by breaking the rules.” The current crisis throws this line of thinking into question, even if the company had passengers sign waivers.

The New York Times reported that the potentially “catastrophic” outcomes of the voyage were made known to company leadership by both employees and external experts. A former engineer was accused of sharing confidential company information after his exodus, which was motivated by OceanGate’s unwillingness to pay for third-party certification. The reporting from the NYT relies on court documents from 2018 that detail the level of awareness the company and its leadership had of the risk faced by those who would go on to make the journey. In tweeting out this story, Laleh Khalili, a professor at the Queen Mary University of London, blamed the “libertarian method of ‘we are above all laws, including physics.’” Coverage that tries to cast the incident as an innocent mistake misrepresents and ignores the steps that were never taken to prevent such an outcome.

I feel sad for the 19yo whose father's hubris landed him here, but a libertarian billionaire ethos of "we are above all laws, including physics" took the Titan down. And the unequal treatment of this and the migrant boat catastrophe is unspeakable. https://t.co/17ax5uySXv

— Laleh Khalili (@LalehKhalili) June 20, 2023

Rush’s approach to the lengths his company should take when it came to prioritizing the safety of his clients and employees and his interest in tapping into the highly valuable industry of deep sea tourism industry are perfect examples of why regulation is needed. If the vessel cannot be found in time to save the crew, the loss will be a tragedy for the friends and family of those who perished. But at a political level, this incident emphasizes the consequences of poor governmental regulation, which can create great burdens for the public. The cost of the search and rescue mission, involving multiple governments, will far exceed what the three individuals paid for their ill-fated voyage. Additionally, it is unfortunate that the government’s failure to regulate the emerging industry led to such an outcome. As the market for extreme forms of tourism, such as space travel, grows, governments must weigh the potential risk against the benefits of allowing such industries to prosper. Lawmakers must contemplate if it is justifiable to spend public money regulating a high-risk industry that caters to only a select few affluent individuals and has the potential to result in substantial public expenditure during a crisis.

Human rights and the inequalities in aid rendered

Related stories

Additionally, the media coverage surrounding the case and the resources expended by the various governments collaborating in the effort reveal a gross disparity in how governments prioritize which lives to save in emergencies. Kenneth Roth, a human rights activist and writer, has been following both cases and tweeted asking if his followers were struck by the different approaches taken to rescue those in the Titanic submersible and “Greek Coast Guard’s pathetic effort to save hundreds of migrants from their obviously precarious boat just before it sank?”

Am the only one struck by the enormous difference between the massive effort to save five people in the Titanic submersible and the Greek Coast Guard's pathetic effort to save hundreds of migrants from their obviously precarious boat just before it sank? https://t.co/YEBwI8GrFP

— Kenneth Roth (@KenRoth) June 21, 2023

The UN Declaration of Human Rights enshrines the fundamental human rights of free movement and seeking asylum. As the search for the Titan intensifies, we can only hope for its discovery and that all those in distress on the world’s oceans and seas receive the same level of assistance as those who were en route to visit the Titanic wreckage.