Football, hooligans, and Yugoslavia: the Maksimir riot and its consequences

The battle between Serbs and Croats in Dinamo Zagreb’s stadium 33 years ago foreshadowed the grim conflict that consumed Yugoslavia one year later.

Dinamo Zagreb face relegation-threatened HNK Šibenik in the Croatian Football League on Sunday. The league has already been sewn-up; another comfortable championship won by the team from the capital. Dinamo regularly dominate the Croat first division, winning every league since 2005 except for the shock win of NK Rijeka in 2017. Think Leicester City’s Premier League triumph in 2016 but next to the balmy Adriatic Sea instead of a car park containing the remains of a dead king.

The trophy will be paraded once more through Zagreb. It is a small capital city typical of central Europe; a Habsburg old town, dedications to Catholic saints, and of course a football stadium. Dinamo’s is named Maksimir after the area of the city it inhabits. Despite being the national stadium of a country that regularly punches above its weight in internation competitions, the stadium is an ageing relic.

A hodge-podge of differing styles, the stadium has three main stands with one curved behind a goal. Fans are far from the pitch; the athletics competitors need somewhere to run after all. The seats are tired and there is no protection from the elements. Toilet facilities are negligible so fans must relieve themselves in the portable toilets dotted around the sparsely populated terraces. It would barely be acceptable for a team in England’s third division, let alone the standard-bearers of Croatian club football on the European stage.

Despite its weary husk, the Maksimir stadium holds a crucial spot in the hearts of many Croatian people, football fans or not. May 13, a day before the non-descript match will be played, a commemoration will be held at the site of a monument dedicated to the Dinamo fans that fought and died in the Croatian war of independence from 1991 to 1995.

Look closer at the plaque however and there is no reference to the outbreak of hostilities in 1991. The monument proudly proclaims the Dinamo supporters’ role in initiating Croatia’s independence, from the stadium riot of 13 May 1990 as well as the sacrifices made in the subsequent war. This memorial is key to understanding the story surrounding the Maksimir riot. Both the events of the day and the unfolding myth surrounding it have passed into not just football legend in Croatia, but into the founding story of one of Europe’s youngest nations.

The Maksimir Riot

On 13 May 1990, Red Star Belgrade travelled to the Croat capital Zagreb to play Dinamo. A top-of-the-table clash, victory for either team would prove to be crucial in deciding the season’s champion. However, political machinations behind the scenes threatened to derail not just the league but the entire fabric of the country.

Croatia’s first multi-party elections had elected a party aiming for Croatian independence just weeks before kick-off. Over in Serbia, the government of Slobodan Milošević was aiming to centralise power in Belgrade away from the autonomous regions. A volatile atmosphere had been created in Yugoslavia. Adding fuel to this, prominent football holligan groups were core supporters of the politicians of their nations. Dinamo’s hooligan group, the ‘Bad Blue Boys’ (BBB) were prominent supporters of Croatian President-Elect Tudzman. Hooliganism was rife in European football at the time and just a month prior the BBB had got into trouble with the police in Ljubliana, Slovenia.

Fans arrived at Maksimir ready to fight. Even before kick-off, Croatian businesses in the city were attacked by Delije, the Red Star hooligan group, and police had to deal with beatings and stabbings. In the stadium, chants against Tudzman were met with chants supporting massacres of Serbs in the Second World War, a war in which fascist Croatia had allied itself with Germany. While the chants themselves were nothing new with hooliganism, the atmosphere generated before the game made following events an inevitability.

The neglected stadium invited opposition fans to bombard one-another from close range. Projectiles toward the Delije led to the Serbians scaling the terraces to meet their attackers. From then on it was chaos. The meagre police presence could do little to stop the fighting. Players who had not yet completed their warm-up watched on as the hooligans engaged one another in brutal style.

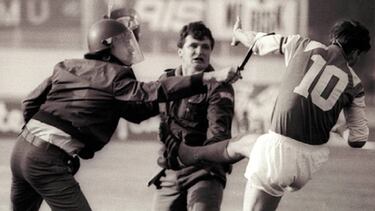

In the most famous moment of the riot, Dinamo captain Zvonimir Boban used his football training to kick a police officer who was accosting a BBB member. The picture has been immortalised as one of the defining images of the disintegration of Yugoslavia.

“Maksimir was the first open confrontation between Serbs and Croats as far back as the Second World War,” says Dr. Mills, lecturing at the University of East Anglia in the United Kingdom and an expert on modern Yugoslav history.

The riot spilled onto the streets of Zagreb that night. In total 138 people were injured, including 79 police officers. Despite no advantage of historical hindsight, news outlets shuddered at the consequences of such a battle.

Everything has gone to the dogs... football fans from two cities have destroyed everything the socialist government built over the past 45 years.

Sportske novosti, 15 May 1990

The beginning of the end of Yugoslavia.

C´ao tifo, 15 May 1990

Newspapers in Croatia, Serbia, and further abroad lamented the damage the riot had caused to the careful fabric of the country They were not shy to blame the other nationality, most clearly seen in reaction to the Boban kick. In Croatia he was a hero, standing up for Croatians (depsite it turning out he kicked a Bosnian); in Serbia he was the arch villain who should be jailed.

But was this press exacerbation justified?

An enduring significance in 2023

Based on these seriousness of these reports it could be assumed that Yugoslavia was on the brink of war. In fact, fighting started over a year after the riot. Though the match was abandoned, the season was concluded with Red Star lifting the title. Another season would be played with Red Star winning again and Dinamo finishing second.

At least initially, Maksimir was another stadium riot in an age of hooliganism. In terms of raw casualties no people were killed, rare for any stadium disaster of the era or even today. Partizan Belgrade, another Serbian team, had fought Dinamo fans earlier in the 1990 season; at that time fan trouble was as constant as the Balkan drizzle.

“[Maksimir] becomes what it is today because of the conflict,” says Dr. Mills. “At the time there were journalists talking about it as as a conflict, as though they were writing a war report for the first time and things like this, that was largely symbolic at that stage.”

Events after the riot elevated the Maksimir riot to mythical status. Members of the BBB and Delije, most notably the infamous Serbian paramilitary-celebrity Željko Ražnatović, also known as Arkan, were some of the first fighters in Croatia’s independence war. The war would last from 1991 to 1995 and claim around 20,000 lives, while the wider Yugoslav wars would kill another 120,000 and displace 4 million people.

The historical revisionism began before the bodies were cold. The monument pictured at the top of the article was not created after the war, but during it in 1994. In it, the BBB explicitly link the riot to their nation’s independence war. 1991 is ignored; according to them and many other Croatians it is in Maksimir where the first blood was shed. Thus, commemoration is inevitably shared between independence and the veneration of hooliganism.

The BBB are not alone in this assertion and the Maksimir riot has become a part of the founding story of an independent Croatia. This belief is echoed in the foreign press too with CNN emphatically declaring in 2011 that this match was one of the matches that “changed the world.”

However, Dr. Mills disagrees with this reading of Maksimir’s importance.

“Although the riot constituted an escalation of tensions, it must be seen in the context of a wave of broader unrest afflicting Yugoslav football. The subsequent armed conflict immeasurably added to its mystique,” he wrote in 2018. “Regardless of its veracity, the myth is an important part of the history of the Yugoslav game.”

Related stories

Barça announce pre-season tour dates

Madrid's US schedule revealed

The hooligan groups continue to exist today. Both the Bad Blue Boys and Delije continue as ‘ultras’ fan groups for their respective clubs, though the increased policing of football matches has ended their fighting capabilities.

Neither club side has played each other since May 1990, but the national sides played one another in 2013. Memories of the war were still fresh with Croatian fans displaying a banner of the Vukovar water tower, a prominent wartime image of defiance against the Yugoslav army. The commemoration of the Maksimir riot on Saturday will serve as another reminder of one of the founding myths of Croatia, misunderstood or not.