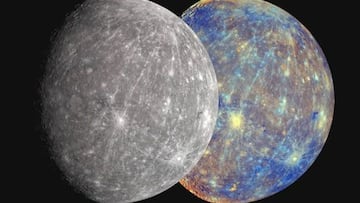

Can Mercury support life? Pioneering discovery detects this crucial clue

Mercury seems at first glance to be completely inhospitable to life because of its proximity to the Sun. But a new discovery has scientists thinking twice.

Are we alone in the universe? That question has been asked again and again, and although life has yet to be discovered on any other planet, space is full of galaxies, stars and planets which means opportunities for extraterrestrial lifeforms. While we humans have been scanning the distant reaches of the heavens looking for that possibility, new revelations within our own neighborhood are presenting ever more chances that we might just find what we’ve been searching for.

At first glance one would think Mercury, the closest planet to the Sun, to be completely inhospitable to life with a daytime temperature of 800 degrees Fahrenheit, hot enough to easily melt lead. Nighttime is a nippy 290 degrees Fahrenheit below freezing as the planet has no atmosphere to retain heat.

But thanks to a recent discovery by a team of scientists, there just may be the conditions to support life on the First Rock from the Sun. According to their research, published in the Planetary Science Journal, indications that salt glaciers exist on the planet have been found.

Can Mercury support life? Pioneering discovery detects this crucial clue

Scientists at the Planetary Science Institute (PSI) maintain that the presence of these glaciers can create the conditions for life, similar to what happens in the most extreme areas of the Earth. “Specific salt compounds on Earth create habitable niches even in some of the harshest environments where they occur, such as the arid Atacama Desert in Chile,” explained Alexis Rodrígez, PSI scientist (via Space) . “This line of thinking leads us to ponder the possibility of subsurface areas on Mercury that might be more hospitable than its harsh surface.”

A discovery that will help expand knowledge about environmental parameters

Related stories

These findings highlight the possibility that microbial life, while it cannot inhabit the surface, it could exist in Goldilock zones in deeper layers of the planet: “This groundbreaking discovery of Mercurian glaciers extends our comprehension of the environmental parameters that could sustain life, adding a vital dimension to our exploration of astrobiology also relevant to the potential habitability of Mercury-like exoplanets,” added Rodríguez.

According to PSI scientist and research co-author Bryan Travis, these glaciers are different from those on Earth and originate from layers rich in volatiles, which remain buried until they were exposed by an impact from an asteroid. “Our [scientific] models strongly affirm that salt flow likely produced these glaciers and that after their emplacement, they retained volatiles for over 1 billion years,” he added.